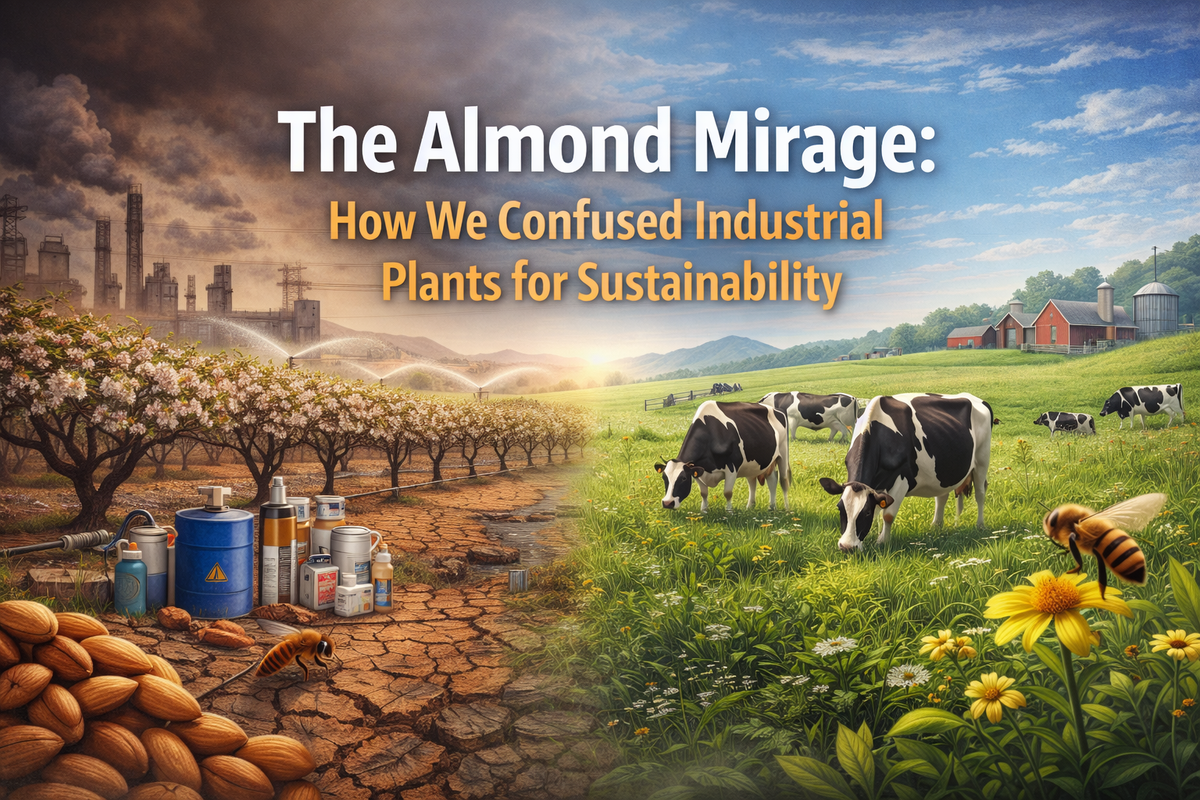

The Almond Mirage: How We Confused Industrial Plants for Sustainability

I was standing in line at a café the other morning, coffee in hand, staring at the now-ritual question: almond milk or dairy. It felt like a moral prompt disguised as a menu choice. One option carried the quiet approval of modern sustainability. The other felt almost apologetic, like admitting a guilty pleasure.

And that moment captured something larger. Over the last decade, we have been trained to equate “plant-based” with virtue and “animal-based” with harm, as if ecology were a branding exercise rather than a system governed by physics, geography, and biological limits. It is a comforting story, clean and emotionally satisfying, but by 2026 the data has become impossible to ignore. The story does not hold.

What we call sustainability today is often just displacement. The damage does not disappear. It moves. It sinks underground, travels across supply chains, and shows up years later in places far from the consumer’s sightline.

Once you look closely, almond milk stops looking like a miracle and starts looking like one of the most successful green illusions of the modern food economy.

Water Use: The Statistic That Lied by Omission

The most repeated claim in favor of almond milk is simple. It uses less water than dairy. The numbers appear decisive at first glance, but they leave out the only variable that actually matters: where the water comes from.

Water Footprint Comparison (Per Liter)

Dairy cows are largely raised in regions where rainfall supports pasture growth. This water cycles through soil, grass, animals, and atmosphere in a regenerative loop. Almonds, by contrast, are overwhelmingly grown in one of the driest agricultural regions in North America.

By 2026, nearly 80 percent of global almond production still comes from California’s Central Valley, a place where water is not renewed on human timescales. Almonds depend on aggressive groundwater pumping, tapping aquifers that formed over thousands of years.

The result is not abstract. Entire sections of the San Joaquin Valley have subsided by close to 28 feet due to groundwater depletion. Infrastructure cracks. Wells collapse. Farming communities lose access to water altogether.

From a systems perspective, almond milk does not reduce water use. It concentrates water destruction in one fragile place while exporting the finished product to consumers who never see the cost.

Bees as Infrastructure, Not Life

If water is the visible stress point, bees are the invisible one.

Every February, around 2.4 million beehives are transported across the United States and concentrated into a single valley for almond pollination. It is the largest managed pollination event on Earth and one of the most biologically extreme.

Pollination Reality Check

For weeks, bees are forced into nutritional monotony while being exposed to pesticide and fungicide residues. Their immune systems weaken. Pathogens spread faster. Colonies collapse shortly after the pollination window closes.

During the 2024–2025 season, beekeepers reported losses exceeding 60 percent. This is not an accident or poor management. It is a structural feature of industrial almond production.

By comparison, a grazing pasture does not require migratory pollination. It creates habitat. Wild bees, insects, birds, and soil organisms thrive in systems built on diversity rather than yield optimization.

One system consumes life as an input. The other multiplies it.

The Chemical and Processing Gap

Almond milk feels clean because it is marketed that way. The production reality is far less elegant.

Almond orchards are among the highest pesticide users in US agriculture, consuming tens of millions of pounds annually. While individual chemicals often pass regulatory thresholds, ecosystems experience them in combination, not isolation.

Tank mixing, the practice of combining pesticides and fungicides, has been increasingly linked to neurological damage in pollinators and long-term soil degradation. What is labeled “safe” in a lab becomes lethal in the field.

Then there is the product itself.

Ingredient Reality

To resemble milk, almond milk must be fortified, emulsified, stabilized, and thickened. Carrageenan, xanthan gum, seed oils, and synthetic vitamins are not accidental additions. They are required.

By 2026, the health conversation has caught up. The link between ultra-processed foods, gut inflammation, and metabolic disruption is no longer speculative. A plant origin does not cancel industrial processing.

Why This Narrative Was So Profitable

The speed and intensity of the plant-based push were never just about climate concern. They aligned too perfectly with economic incentives to be purely altruistic.

You cannot patent a cow. You cannot own grass, sunlight, or reproduction. But you can patent processing techniques, additives, lab-grown growth factors, and proprietary formulations.

Control Comparison

Moving food production away from land-based systems and into controlled environments creates predictable margins, defensible intellectual property, and investor-friendly scalability. To make that transition socially acceptable, the cow had to become the villain.

The narrative did the work. The incentives followed.

The Quiet Return to Regenerative Reality

What has changed by 2026 is not demand for alternatives. It is understanding.

People are learning that sustainability is contextual. A solution that works in one geography can be destructive in another. Biology, when respected, often outperforms industrial optimization over time.

Regenerative dairy, when done correctly, restores soil structure, increases water retention, supports biodiversity, and converts grass that humans cannot eat into dense nutrition.

System Outcomes

This is not nostalgia or denial of industrial dairy’s problems. It is a recognition that living systems behave differently than factories, and that pretending otherwise has consequences.

A More Honest Recommendation

If you want to make an environmentally meaningful choice, stop outsourcing ethics to labels. Buy fewer processed substitutes. Buy closer to where you live. Support systems that fit their landscape rather than forcing nature to comply with global demand curves.

Find a local dairy farmer. Look for regenerative practices. Ask how the animals live, how the land is treated, and how water is managed.

It is better for your gut. Better for pollinators. Better for water systems. And far more honest about the trade-offs we cannot escape.